Roland Meyer, Saramani and a Cambodian Love Affair

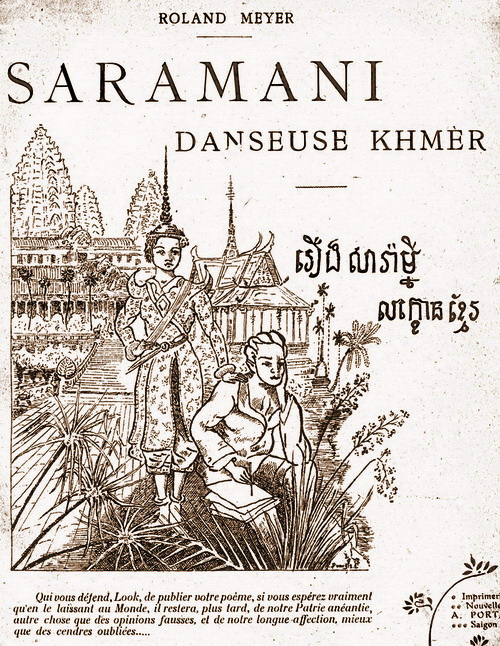

To the glory of the land that captivated my youth

I dedicate this poem, written under its beautiful sky.

With the fervor of a saint,

I have taken it upon myself to tell the world

of the beauties of the kingdom of Cambodia

and the virtues of the Khmer people.

Thus I pay my debt of gratitude for their warm hospitality.

The opening lines of Roland Meyer’s epic tale of Cambodia: Saramani

Article by Kent Davis

At the end of the 19th century, a young French boy dreamt of finding a tropical paradise. Books about Pacific island adventures and the discovery of lost cities in the dense jungles of Southeast Asia fueled his imagination. Soon, the urge to travel was irresistible but what set this young man apart from thousands of others is that he shared his stories.

Roland Théodore Emile Meyer was born in Moscow on July 10, 1889. His parents moved to Paris where, after his education, he enrolled in the Indochinese colonial service in 1908 at the age of 19.

Meyer first served for three months in Saigon as a cabinet aide to Governor-General Paul Beau in Saigon. Upon moving to Cambodia in 1909 Meyer’s life changed forever as he immersed himself in the history, language and lifestyle of the modern descendants of the ancient Khmers.

Unlike other colonials, Meyer chose to assimilate with the indigenous culture surrounding him, learning the local language, customs, religion and even setting up his home among the natives outside the French quarter of the town. Meyer was a living example of a visitor who “went native”, much to the surprise of some of his fellow colonials. In 1912, Meyer published Cours de cambodgien, the first book to teach the Khmer language to Francophones.

With Phnom Penh still a small town, Meyer soon met others who admired and respected the legacy of the great civilization that surrounded them. His small circle of friends, many of whom were founding members of The Angkor Society, came to shape the way the world sees Cambodia. They included Jean Commaille, the first conservator of the Angkor site; Henri Marchal, the second Angkor conservator who took over Commaille’s duties when he was murdered by robbers; and Charles Gravelle, director of the country’s branch of the Bank of Indochina and an avid writer himself — all men whose influence is still with us today.

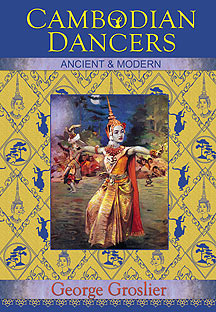

Another associate embarking on a stellar career in Cambodia was George Groslier, an artist and writer two years older than Meyer, who arrived in Phnom Penh in 1910 on an educational assignment. As it turned out, both young men were captivated by a living, breathing vestige of the ancient Khmers; the sacred Cambodian dancers who lived, sequestered, in the royal palace as part of the king’s harem.

On returning to France in 1913, Groslier published Danseuses Cambodgiennes, Anciennes et Modernes, the first formal study of the sacred artistic tradition. Meyer’s experience and vision of the dance and dancers, however, went even deeper and was far more intimate.

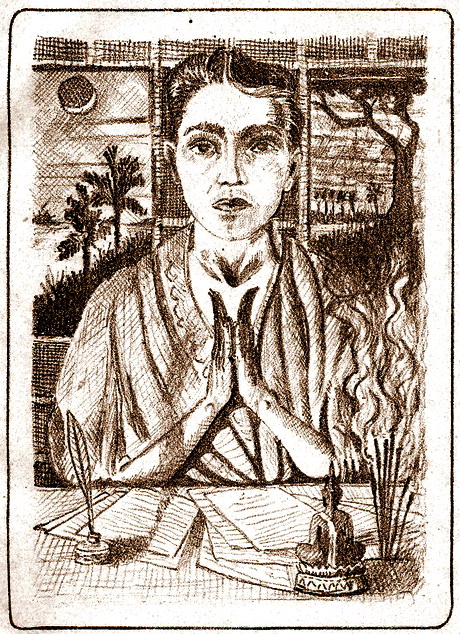

Meyer told of a seemingly forbidden romance between East and West — between a royal dancer in the king’s harem named Saramani, and a French boy who came to Indochina to seek his destiny. The boy, like Meyer himself, “went native” and adopted the Khmer name Komlah, which means bachelor. Through Saramani and her family, Meyer (often writing as Komlah) relates a detailed picture of love and life in colonial Cambodia.

For a decade, Meyer recorded his notes in his personal diaries, shaping a tale in which it’s difficult to tell fact from fiction.

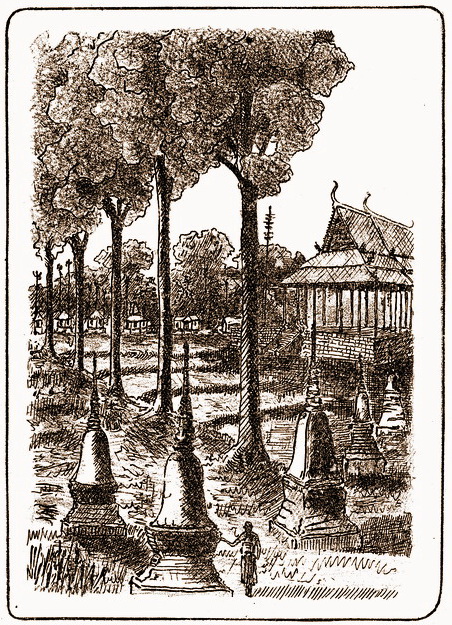

In 1919 Meyer published Saramani, Danseuse Khmèr in Saigon. His epic account of Cambodia stretched from the primeval formation of the land tens of millions of years ago, to the peak of the Khmer civilization at Angkor Wat, ending in the modern colonial capital of Phnom Penh. He records the lives of all he encounters on Cambodian soil; rice farmers, fishermen, immigrants, colonials, dancing girls, poor peasants, wealthy merchants, royal servants and even kings.

Saramani grew to a massive work of more than 180,000 words exploring many controversial events in the guise of “fiction”. Meyer’s views of colonial lust, capitalistic greed and royal decadence were upsetting to some, to say the least. The same year of its release he transferred to Laos, perhaps out of necessity to escape local consequences…or perhaps to escape romantic entanglements that may have inspired some of the scenes throughout the book.

Was Saramani a real person? Were the book’s fantastic events based on reality or imagination?

Meyer never revealed this but his exceptional accuracy, attention to detail and congruity with historical events implies that there is much more than fiction in his account.

Meyer worked with the French civil service until retirement. Coinciding with the French Colonial Exposition of 1931 in Paris he published two more books, Komlah, visions of Asia and French Indo-China. Laos. While Komlah relates many more personal impressions in Indochina the second title is a rather dry analysis of the Laotian country.

In 1952 his friend M. Gerard published his final work, a collection of short essays titled Le propos du vieux colonial.

Sadly, like many great men of the French colonial era, Meyer’s trail vanishes late in life. I don’t know where he died, where he is buried, if he has any descendants or what became of his archives. A sad loss to Cambodian, French and literary history.

If any readers have additional information please contact me kentdavis at gmail dot com.